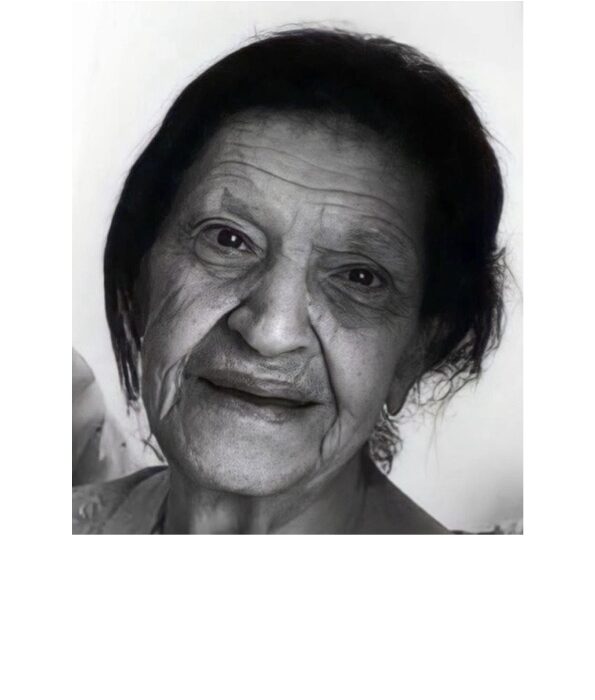

Six months ago, on Thursday 17 February 2022 to be precise, my mother passed away with her final wish being granted: to die in her own bed while still in control of her faculties. Having reached the grand old age of 95, it would be ridiculous to claim her death was unexpected or untimely. Nevertheless, as her immediate family, we still felt her loss as a much loved and treasured matriarch who gave us all more love than we ever gave back.

Amongst many, many family members and friends, we, her six children, have collective as well as individual memories of her. This is how I personally remember my mother, Ruwaida (Ruweida) Zamamiri.

She was a kind, gentle, loving and giving woman who adored her children, grandchildren and great grandchildren. She knew everyone’s date of birth and memorised dozens of telephone numbers. She was an excellent cook and loved to entertain visitors, always insisting they had another helping. She had a wicked sense of humour and when she saw or experienced something funny, she went into fits of quiet infectious laughter that brought out the little girl in her. Above all, she always carried herself with dignity and went to great lengths to hide her sadness, disappointment, anger or frustration.

But Ruwaida was more than that; much more. Ever since I could remember, I sensed her love, care, compassion, and beauty through her hands. My earliest memory of her when she was in her late twenties/early thirties, I loved to sit and watch her put on make up and use hand cream from a special jar that revitalised her hands’ skin. They were beautiful, soft and elegant hands. She completed her make up session by wearing her everyday gold jewellery which consisted of a wedding ring, another ring she wore on the same finger as her wedding ring, and a third ring on the third finger of the opposite hand. Finally, she wore her gold wrist bands. Memory fails me to say how many bands she wore but, I believe they were about 6 which she split evenly between the two wrists. On special occasions, she wore necklaces she kept in a drawer of her dressing table. The hand jewellery, plus a wristwatch, were worn on daily basis for years and years and only very occasionally did this arrangement change. By the time she passed away, she had given all her jewellery to women she cared about greatly such as my two sisters Nawal and Najwa. I managed to keep one of her watches for sentimental rather than intrinsic value.

Ruwaida was a talented sketcher and painter. Between leaving school and getting married, she was allowed to attend an abbey in Jerusalem where she learnt to paint porcelain under the tutelage of an artistic priest who was in charge of this art school. The output of the students was mainly hanging plates and cups aimed at the tourist market. Ruwaida kept a few examples of her work which hung in various places in our house. A couple of examples of her work survive to this day in the care of my brother, Samir.

Born left-handed, her schoolteachers insisted on her swapping hands and write with her right hand. As a result of this outdated teaching habit, Ruwaida became ambidextrous, able to swap hands and do just about anything equally well with both hands; all except eating which she insisted on using her right hand. This dexterity proved useful on many occasions, which she used to amuse and impress us as children. For example, she knitted, leading with one hand and then she swapped over and knitted with the other. It doesn’t seem like much but, I was always impressed with such a gift. She also delighted in telling us the story of how father offered to teach her to drive but she always declined because she was convinced that because of her dual use of both hands she might confuse her left from her right. We all knew that was a ridiculous excuse and so did she but, that was her version of reality and none of us challenged her on it.

At a personal level, like all children, I found solace and refuge in her arms but I particularly loved the sense of comfort and security I gained from having her cup my face with her hands or when she ran her fingers through my hair as I rested my head on her leg. Having lived in a period where corporal punishment by parents and teachers was a normal everyday method of control and discipline for wayward children, I had my fair share of smacks, on the legs, bottom, back of the head and the face, I am so grateful and appreciative of the fact that my mother’s hands were never, ever used to control or punish my infractions. God knows I gave her enough reasons to do so on dozens of occasions, but she always reverted to shouting empty threats which she never carried out.

As I grew up into my teens, my mother’s hands grew older with me. In place of those delicate, manicured hands emerged strong and over-worked hands looking after a family of six children and a demanding husband. However, even without the lustre and delicacy of young hands, what I experienced was the sight of honest, reliable and highly proficient hands that mastered many skills mostly on domestic matters, the best of which was her mastery of many dishes. My love of cooking and baking is all due to her influence. Although she never wrote down or referred to recipes, she was always able to recreate the most complex of dishes purely from memory and experience. When I asked her how do you roll up vine leaves, what spices to use for a stew, or how many eggs she needed for a specific cake, her answer was always the same: I don’t know, just watch me and you will learn. My love for cooking was born by watching those wonderful hands at work.

I finished school, went away to university and I saw my mother’s hands less and less frequently. The first time I noted the marked change in the state of her hands was when she was coming out of her fifties and into her sixties. The veins in her hands made an appearance, each carrying vital blood from her heart to her fingertips and back, as well as stories of a woman who raised six children who gifted her with more children to hold, love and rock to sleep. Her hands assumed a different type of beauty and what they lost in dexterity due to age, they more than made up for it with sensitivity and compassion. Not that she did not try to delay ageing by all reasonable means. Like all women and some men, Ruwaida tried to keep old age at bay. She loved going to the hairdressers; whenever I announced I was coming to visit her, the only thing she consistently asked for was her favourite Chanel 5 perfume; and she still used moisturising cream well into her eighties.

Throughout her eighties, I was lucky enough to find myself working in Cyprus while she lived in Jordan, a mere one hour flight away. She was a widow by then, which freed her to travel without the encumbrance of an ailing and very demanding husband. She was also popular with children, grandchildren and now great grand children who always insisted on visiting her as soon as they landed in Jordan. The highlight of our visits would be to gather at her apartment for a lunch or dinner and enjoy her cooking again. With the advancing years, her ability to entertain multiple people was no longer there so, she trained her hired help to do the physical elements of food preparation while she retained the final flourish of putting the meal together with those ailing, yet skilful hands.

Last time I saw and experienced my mother’s hands was at my nephew’s wedding in Dubai. I saw her for a few hours only as I had to travel to England for Faye’s graduation ceremony. But I had a chance to kiss her thin and beautiful hands. It was July 2018, one month before I was diagnosed with liver cancer. Ruwaida was now in her early nineties and unable to travel. I too was unable to travel so by necessity, we limited our communication to weekly phone calls when both of us were physically up to the task. Oh, how I regret missing the chance of seeing her during those final four years and not being with my siblings holding vigil by her bedside as she drew her last breath on this earth! I am eternally thankful to my sister Najwa who called me and held the phone to my mother’s ear for me to say goodbye to her just before she passed away. She was unable to talk but I knew she was bidding me a final farewell.

One last thing about my mother’s hands. Ruwaida was not the over-demonstrative type; she kept her emotions in check and showed them to those she trusted and felt safe with. Nevertheless, her hands never lied or hid her true feelings. She gesticulated like an Italian with her own set of gestures that only she could master. They ranged from the very funny to the absolute heart-wrenching feelings. Only Ruwaida would make a toddler dance in her lap by holding the child with one hand and using the other to pirouette a dance movement. She also told us her children what she thought of our behaviour by a hand gesture known to us only. But the gesture that I witnessed once and I am so glad I never did again was her telling me and my sister Nawal (we were six and eight years old at the time), that we had lost our one-year-old brother. Even at the age of six, that gesture told me of the immense loss we had suffered before she had a chance to use words to confirm what my child’s mind and heart had received and processed. I will spare you and me the discomfort of reading the description of that awful gesture.

Finally, I urge you to listen to a song written and performed by the amazing soul singer Bill Withers. The song is called ‘Grandma’s Hands’; it touchingly conveys how I feel about my Ruwaida and my unconventional way of describing my relationship with her. The song is only two minutes long but convey so much love and affection.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TdrChyGb574

Ruwaida, wherever you are, whatever you’re doing, I hope your hands are still as beautiful as they were in your twenties and as loving and wise in your nineties.

That is a beautiful piece of work Mufid and confirms that it is what we do rather than what we say is what defines us. Your mum was a beautiful lady, inside & out.

That was a beautiful piece Mufid. It confirms that it is what you do that counts, not what you say. Your mum was a beautiful lady, inside & out.

A lifetime of mothers love in those beautiful hands.

This made me cry but I’m happy I can still picture her hands xxx

Such a lovely tribute to an amazing lady. We will remember her ❤️

What a lovely and heartfelt tribute to your Mother, Ruwaida, whom I had the pleasure of meeting only once in London, in fact if I remember correctly on Clair’s dad boat on the Thames. She left a mark on me, because although I was a complete stranger to her, the very fact of my presence there as the friend of her children, was more than enough to show me such honest and unselfish love, respect and affection. May she rest in peace eternally.